WHY READ THIS ESSAY?

No, The title of this essay is not a stupid statement. There’s actually zero objective evidence at all for Mecca’s existence at the time of Muhammad! Everything we have ever been told comes to us from Muslim apologists living 1,400 kilometres away and writing hundreds of years after the facts.

Research from world-renowned secular academics from Princeton, the University of London and Oxford University who have developed great insight into the geography, history, culture, politics, religion and languages of the Middle East is now challenging long held assumptions about the presence of Mecca in the 7th Century.

This essay is simply a summary of my investigations of their essays, books and publications, focusing specifically on the history of Mecca.

1. INTRODUCTION

First up for unfamiliar readers, here is a very brief version of the official story of the city of Mecca: Prior to the rise of Islam, Mecca was the centre of a thriving trade empire going back hundreds of years. It was situated on the crossroads of significant trade routes between India and Europe. It was the home of the Ka’ba, a famous temple full of idols. It was Muhammad’s home town and dominated by his tribe, the Quraysh. Mecca was the town Muhammad was born into, grew up in, and from where he began his ministry. Mecca eventually became the spiritual base for his new religion, Islam. It went on to became the global centre of Islam after his death and remains so today as Islam’s number one pilgrimage site and the direction of all prayer. The Qur’an calls it the mother of all cities (surah 6:92).

This is the account of Mecca you will find in the Hadith and Sira literature that forms the basis of Islamic traditional history. Most western encyclopaedias, most biographies of Muhammad and most histories of religion rely on these as their sources. It is akin to trusting everything early Christianity said about itself. This is the history of Mecca, Muhammad, the Qur’an and Islam that I also subscribed to before I began researching those academics that run, research and lecture in the world’s leading schools of Islamic and oriental studies. We Are only now beginning the long and arduous journey of applying the skills of higher criticism that were honed on the history of Christianity to these Islamic histories.

Now let’s step outside all Islamic traditional histories. What do we actually and objectively know about Mecca? What can we glean from the ancient independent historical sources and modern objective research? Do they verify Islamic history? Did the city exist in the early 7th Century as claimed? Was it a major trading centre? Was it a city of religious pilgrimage? Did Muhammad live there? Is that where Islam started? These are the questions that should be asked by every historian of Islam, but for reasons of political correctness, post-colonial guilt, fear of backlash, and fear of being labelled Islamophobic, they are rarely asked. The current lack of intellectual rigor is embarrassing. In this essay all these questions will be answered using objective historical sources alone.

Spoiler Alert: After several years of research I have concluded that Mecca was not a centre of trade, was no centre of religion, had nothing to do with Muhammad, and quite probably did not exist in the era of the birth of Islam. This opinion is shaped in part by the influential scholar of Islam, Patricia Crone, who was Professor Emerita in the School of Historical Studies at Princeton University, via her excellent book Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam. Crone spoke 15 Middle Eastern languages, many of them ancient. She was able to read a whole range of original documents in their original languages. She was a towering figure in the birth of the higher criticism of Islam. I have also made use of Did Muhammad Exist by Robert Spencer. Other references have come from The Idea of Idolatry and the Emergence of Islam by G.R Hawting, In the Shadow of the Sword by Tom Holland, Robert Hoyland’s Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam, The Hidden Origins of Islam by Karl Ohlig and Gerd Puin, and Qur’anic Geography by Dan Gibson.

One day in the mid 1980’s while teaching the history of Mecca at Princeton University, Patricia Crone was asked by her students as to what exactly the Meccans traded in. It was a simple question so she decided to find out. However, the more she dug into the two sources of traditional Islamic histories about Mecca, the official biographies of Muhammad (Sira) and the official commentaries of his actions, sayings and approvals (Hadith), the more the story fell apart. What commodities could have made the city wealthy? Where did they come from and who was buying them? The more she investigated, the more things did not make sense.

Intrigued? I was too. So let’s investigate.

Using the above sources, this essay has been divided up into the following topics:

- The fallibility of Ibn Ishaq and the Sira literature

- The fallibility of the Hadith literature

- Mecca in the Qur’an

- Mecca’s geography and climate

- What the ancient historians said about Mecca

- History of the Arabian spice trade

- Was Mecca a pilgrimage site?

- Birth of the Arab Empire

- Birth of the Islamic religion

- The location of the original Arabian city of worship

2. THE FALLIBILITY OF IBN ISHAQ AND THE SIRA LITERATURE

First of all we need to see if the official story of Islam and Mecca is accurate or not. For this we will first look at the biographies of Muhammad, otherwise known as the Sira literature. We will start with the oldest and most referenced complete biography of Muhammad. It is by the Abbasid scholar, Ibn Ishaq. Muhammad is supposed to have died in 632AD and Ibn Ishaq died in 773AD. So this history was collated from oral recollections some 150 years after the facts. Tragically, none of Ibn Ishaq’s original writings survive. They only come to us from an abbreviated version edited by a man called Ibn Hisham some 50 years later again.

Even though there are other Sira authors, nearly every Islamic biographer to this day depends to a large extent on Ibn Ishaq’s account, via Ibn Hisham’s editing. As noted already, nearly every secular western encyclopaedia article also uses Ibn Ishaq as its guide without checking its accuracy against external historical markers. Ibn Ishaq is therefore a key gatekeeper of Islamic history, and of Mecca’s history. If he tells the truth then Mecca is exactly as Islam says it is. If he is not, then Mecca, Muhammad, the Qur’an and the entire religion of Islam itself are on shaky ground.

So is Ibn Ishaq’s biography accurate? We don’t have to go far to find the answer. Even in his own day many of his contemporaries were very concerned about his writings. Ibn Hashim himself warned that he had to sanitise Ibn Ishaq’s work. Of the prophet’s life he left out things which is disgraceful to discuss, matters which would distress certain people: and such things as al-Bakkai (Ibn Ishaq’s student) told me he could not accept as trustworthy (The life of Muhammad by Ibn Hashim, Page 691, Ibn Hisham’s notes paragraph 3). On page xxxvii of the same document there are numerous reports of other authorities who doubted the trustworthiness of Ibn Ishaq’s work including the renowned Hadith specialist, Ahmad ibn Hanbal, as well as Abdullah b. Numayr, Al-Daraqutnl, Abu Da’ud al-Tayalisi and Yahya b. Sa’id.

Internal evidence paints its own air of suspicion. The Qur’an states repeatedly that the prophet of Islam did no miracles (surah 30:58), and that one of the primary criticisms of Muhammad was that he could do no miracles (surahs 6:37, 10:20, 13:27). The miracle of Islam was to be the divine origin of the Qur’an itself (surah 29:51). However, by the time of Ibn Ishaq’s biography Muhammad was busy performing many miracles! He was multiplying food for hungry hordes, miraculously restoring injured eyes, drawing water from dry ground, and shooting out lightning from a pickaxe. All of these accounts contradict the Qur’an. If they were true then why weren’t they included in the Qur’an and proving Muhammad’s status as divine prophet? This would then mean we cannot trust the Qur’an. If they are false then we cannot trust Ibn Ishaq. In addition, many of these stories sound vaguely similar to the miracles of Jesus Christ as found in the New Testament. It is clear that the process of mythologising the past was well underway by the time the first biography was written. The 150 year gap was too long to find and record the truth.

Criticism of a more theological kind also comes from within the modern Muslim academic community. Here are some of their concerns. First, Ibn Ishaq was from the Shi’a side of Islam, favouring Ali over all the other contenders to the caliphate. That’s a big credibility problem if you are a Sunni Muslim. Second, he held the view that man has free will, which contrary to the Quran’s teachings. Third, his chains of transmissions, the list of authorities who were keepers of the oral history who were called the Isnad, were defective because he didn’t name them all. Fourth, he used reports of traditions gathered from Jewish sources, another big mistake. Fifth, his report about Muhammad’s first revelation contradicts all the other Hadith literature. Sixth, there are several stories in Ibn Ishaq’s writings which are never found in the rest of the Hadith literature.

Modern historians, such as J.G. Jansen (The Gospel according to Ibn Ishaq), have found that none of the contents of Ibn Ishaq’s works are confirmed by external sources, inscriptions or archaeological material. None. He also found that verifying testimonies from non-Muslim contemporaries do not exist. This includes any reference to Mecca.

Jansen follows up these two disturbing facts with the pithy observation that even though Ibn Ishaq astonishingly knew the exact month of every act in the drama of Muhammad’s life, he forgot to include the lunar months. The pre-Islamic calendar had to incorporate an extra month every three years as it ran on a 354 day lunar year cycle. Over the ministry of Muhammad there were 6 or 7 of these lunar months. Yet Muhammad apparently did nothing during any of these 6 or 7 extra months, not a single thing. Knowledge of the pre-Islamic lunar leap year had obviously been lost by the time of Ibn Ishaq so he didn’t think to include it in his dating system. This, along with the proliferation of miracles, suggests Ibn Ishaq was creating a story, not recording it.

Modern investigation into the rest of the Sira literature is now extensive, and the conclusions from the world’s leading researchers is not good. In 1983 Professor M. J. Kister wrote that The narratives of the Sira have to be carefully and meticulously sifted in order to get to the kernel of historically valid information, which is in fact meagre and scanty. (The Hidden Origins of Islam p. 240). Andrew Rippin, Professor Emeritus of Islamic History University of Victoria Canada, commented that The close correlation between the Sira and the Qur’an can be taken to be more indicative of exegetical and narrative development within the Islamic community rather than evidence for thinking that one witnesses the veracity of the other (Ibid p. 249). G. R. Hawting, lecturer at the School of Oriental and Asian Studies University of London, worries that the meaning and context supplied (via the Sira and Hadith literature) for a particular verse or passage in the Qur’an is not based on any historical memory or upon secure knowledge of the circumstances of revelation, but rather reflect attempts to establish a meaning. (Ibid p. 250). I could go on extensively with a much larger list of researchers who cast grave doubts on the veracity of the Sira literature. They have all come to the same conclusion as the three researchers quoted above; that the Sira is a product of Abbasid myth building that took place hundreds of years after the facts, rather than faithful history. We will find out a lot more about these mischievous Abbasids later.

If Ibn Ishaq and the other biographers of the Sira literature cannot be trusted when talking about the prophet of Islam, we simply cannot trust them on issues relating to Mecca as well. So let’s now turn to the Hadith literature, which is much more extensive than the Sira. Perhaps it contains some accurate information about Mecca.

3. THE FALLIBILITY OF THE HADITH LITERATURE

The Hadith literature are the official commentaries that provide us with the words, actions and approvals of Muhammad. They rank second only to the Qur’an in Islamic theological and political authority. They encompass a vast amount of clarification and traditional history interpreting the Qur’an, Muhammad’s life and the origins of Islam. It is the Hadith that creates and then makes sense of the utterances of Muhammad. It is the Hadith that most people rely on as authentic history about early Islam and the history of Mecca. It is the Hadith that tries to bring logic to the utter confusion most people are left with after reading the Qur’an on its own. Because of this confusion the Hadith is the de facto primary source of authority in the religion of Islam.

But like the Sira biographies, the Hadith commentaries were also written two to three centuries after the facts, and once again largely by Abbasid scholars over in Persia. It’s like penning the very first history of the American War of Independence from 2018 through to the year 2100AD, relying only on fifth to tenth generation oral memory. This gave the Abbasids more than plenty of time for mythologising of the type we saw above.

Anybody within Islam could write a Hadith in those restive first two to three centuries, and write they did. They could tell the world what they recalled from a trusted chain of oral authorities, the famous Isnad sources, about the words, actions and life of Muhammad. In the process it turned out that the vast majority were only written to justify factional rivalries and disputes. It didn’t matter if the Hadiths contradicted each other. It mattered more that the chain of Isnad was pure. They eventually became a laughing stock, the original fake news. They contradicted each other to the point that one dedicated scholar, Muhammad al-Bakhari, another Abbasid scholar from Iraq (d. 870AD), decided to find as many as he could, ditch the fakes and compile a trusted history of the past. He aspired to creating an authentic exegesis of the Qur’an, Muhammad and Mecca. He travelled far and wide, collected some 600,000 alleged sayings of the prophet, and then ditched all but 7,225 that he believed could be trusted. He is today revered as the most trustworthy source of Islamic history, and therefore the history of Mecca. Five other collectors of Hadith are also canonised along with him, including his disciple Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj who collected hundreds of thousands more Hadiths and discarded all but around 4,000. However, we have a problem with finding original copies of these two scholar’s writings. The oldest surviving copy of any piece of al-Bakhari’s works is from hundreds of years after he performed the great cull.

With the recent application of the tools of secular higher criticism to the story of Islam, more and more scholars are delivering body blows to the credibility of the Hadith writings. New discoveries and cold hard theological objectivity has allowed a much more rigorous search for fakes than al-Bakhari religious sensitivities allowed for. The towering 20th Century academic, Joseph Schacht, called the Hadith literature a fiction perhaps unequalled in the history of human thought. Ouch! Schacht also argued that the fabrication of the Hadith came from a literary convention, which found particular favor in Iraq, whereby Abbasid authors/scholars would put their own doctrine or work under the aegis of an ancient authority. The ultimate prestigious ancient authority in this context was Muhammad and around 750AD scholars in Kufa, followed in a few years by the Medinese began falsely ascribing their new doctrines back to earlier jurists, and over time extended them back to Muhammad. In other words they invented all the words, life and actions of Muhammad to justify their own agenda.

The fabrications are relatively easy to spot. The amazing detail in the Hadith, the exact words spoken, the time of day, what they ate, how they travelled, who was present, the theological disputes they were defending and much more, all combine to give the Hadith too much authenticity. They are too precise, lacking in context and contradictory. What mattered most was the air of authenticity given by the alleged chain of oral authorities. The motivation was simple. They were written by very clever legal scholars living hundreds of years after the facts, who were designing a chain of historical transmission that, in the words of Dr Umar Bashear, grow backwards to justify a new legal code for a brand new empire, and one that would wrestle power from their political masters, the Caliphs (Abraham’s Sacrifice of His Son and Related Issues p. 277). Their creation of a religious prophet, a religious city, a religious text, a religious holy language a religious history and a religious destiny gave them the upper hand in the endless power struggle that was Middle Eastern politics. Supreme power within the realm of Islam would from then on rest with them, the religious scholars, not their political masters. The evidence and legacy of their work can be seen in the modern call to Jihad, and the fear of it within the political class of most Islamic countries.

It is these clever writers of the Hadith that I will now summarise to demonstrate that they did not write an authentic history of the Qur’an or Mecca. I will use Crone’s excellent examination of the various Hadith explanations of surah 106, a surah that the Hadith literature claims to talk about Mecca.

For the accustomed security of the Quraysh

Their accustomed security [in] the caravan of winter and summer

Let them worship the Lord of this House

Who has fed them, [saving them] from hunger and made them safe, [saving them] from fear.

Note: To demonstrate how much the English version of the Qur’an is influenced by the stories that the Hadith commentaries created and not the other way around, the term accustomed security in line one above is a Hadith interpretation of the word ilaf, which has no known meaning. The Hadith writers had to give it a meaning or the surah would be utter confusion. In addition, all words in brackets are also extra to the original Arabic Qur’an.

Now, what do the different Hadith writers say about this surah. The following is what Patricia Crone found out…

Fakhr al-Din al-Razi says the journeys are both pilgrimages to Mecca (Mafaith, VIII, 512). However, Ibn Abbas says the journeys are to Ta’if in summer and Mecca in winter (Jami, XXX, 171). Most other commentators treat them as trading journeys to Syria, or Yemen, or Rum, or Iraq, or even Ethiopia. Ibn Habib and others say the surah is about a pre-Islamic famine (Munammaq, pp. 263)

Baydawi says they are being told to worship because they were blessed in their journeys (Anwar, II 620). But Ibn Qutayba says they worship because the Ethiopians did not harass them or Mecca on their journeys (Musbkil al-qur’an, pp. 319). Al- Tabari says they are being told to worship God as much as they travel (Jami, XXX, 199). Muqatil and Qummi both say they were being told to worship because Allah put an end to these journeys, with Ethiopians or others having taken over the provisioning of Mecca (Tasfir, fol. 253a, Tasfir, II, 444).

Ibn al-Kalbi says the fear referred to was a fear of the road. Bakkar says it was fear of the Ethiopians (Bakkar in Sutuyi, Durr, VI 398). Traditions from Tabari say it was a fear of leprosy (Jami, XXX, 200). Razi says it was fear that the Caliphate might pass from the Quraysh tribe (Mafitab, VIII, 513)

This is the type of “history” you must wade through when reading all the Hadith literature. It is clear, just from this tiny snippet that we are not dealing with historians, but story tellers desperately trying to make sense of an opaque script. This is confirmed by the fact that the later the Hadith was written, the more details of the story are presented and the more clear the chain of oral transmission. This is the opposite of normal historical manuscripts and looks more like a giant game of Chinese Whispers than of total recall. The prolific scholar of Islam, Ibn Warraq, correctly says that large parts of the Sira and Hadith were invented to account for the difficulties and obscurities found in the Qur’an (The Hidden Origins of Islam, p. 247).

Clearly then we cannot trust both the Sira or the Hadith literature as a source of accurate information about Mecca. This leads us back to the oldest book of Islam, the Qur’an. Can it finally tell us the truth about Mecca?

4. MECCA IN THE QURAN

Mecca’s current status is central to Islam and the Arab-centric nature of Islam. After the Qur’an, it is the epicentre of Islam. All historical, physical and theological roads lead to this mystical city. All Muslims the world over must pray in its direction. It is variously described as the mother of all cities, the centre of the world, the oldest city in the world and the city first established by Abraham as the first place of monotheistic worship.

It comes as something of a surprise then that what is taken for granted today to be Mecca is only mentioned twice in the Qur’an. Assuming the following references are talking about the same place, surah 48:24 describes it simply as the valley of Makkah, and surah 3:96 simply calls it Makkah. Sometimes it is also called Bakkah. Bakkah is a Semitic word that means The Valley of Weeping.

This startling lack of Qur’anic references is part and parcel of the structure of the Qur’an, it is an utterly confusing and frustrating book to read on its own as it rarely says who is speaking, who is being spoken to and what the context is. That’s why Muslim scholars invented the Sira and the Hadith. The Qur’an only mentions nine different geographic place names in over 149,000 words. This infrequency of geographic references, at the rate of one every 2,299, is one tenth what it is in the New Testament. One suspects this is deliberate. It’s as if the Qur’an is trying to avoid pinning down its original location. You will find out why as you read on.

Here is the full list of all place names in the Qur’an, with frequencies:

| Location | Frequency |

| Thamud | 24 |

| Ad | 23 |

| Midian | 7 |

| Yathrib (Medina) | 2 |

| Valley of Bakkah (or Makkah) | 2 |

| Tubb’a | 1 |

| Al-Ras | 1 |

| Hijr | 1 |

And that’s it for a 400 page book! It’s not much to go on for any historian trying to find the truth about Mecca. But there are clues from that list, so let’s look at them now.

The Midianites were descendants of Abraham and lived at the top of the Red Sea. Moses is said to have lived with them for 40 years (Exodus 2:15-23). These people are easily located in lower Jordan. They lived nowhere near modern Mecca.

Ad (sometimes Aad) is a foreign word to Arabic. Specific details about the people of Ad are given in surah 7:65-72, surah 11:50-60, surah 26:123-140 and surah 89:6-14. From these passages we glean the following clues: They built high alters and monuments, they had cattle, springs and gardens, they had a leader called Hud, they had strongholds and homes in the rocks, they built a many-columned city called Iram and they lived close to the people of Thamud. From those clues we can safely say that the Ad knew a lot about Greek columned architecture, they were versatile farmers and lived in the rocks and mountains. This is definitely not a description of an Arabian city but a vivid picture of Petra. Nothing else anywhere further south fits the bill as Petra was the final outpost of Hellenistic culture and architecture. If it was Petra, and the Qur’an says the Thamud lived close by, then the Ad, Thamud and Midianites were all in lower Jordan or at the top of the Red Sea, not deep in the Arabian Peninsula. This was the centre of the land of the famous Nabataeans, the one group of Arabs who were culturally sophisticated, highly literate, commercially savvy and downright wealthy because they dominated the trade to Europe.

This view is reinforced by the evidence for Thamud in the Qur’an and the Hadith. The Qur’an says Thamud had gardens and water-springs and tilled fields and heavy sheathed palm trees (surah 26:141-159) and they hewed the rock into dwellings (surah 7:73-79). This is clearly a description of Nabataean rock excavating culture and its agriculture. Thamud’s location in the Hadith is given as Al-Hijr (Bukhari 4:562 and Fiqh us-Sunnah Hadith 4:83). Al-Hijr was the southern-most outpost of the Nabataean Empire, 800 kilometres north of Mecca. It is full of Nabataean tombs and is on the World Heritage list. The Qur’an’s repeated references to Thamud demonstrate its importance to the Qur’an’s writers.

It would be no accident that the Nabataeans feature in the Qur’an, howbeit under a different name, having their status theologically transferred to Mecca by the Abbasids. It was they who controlled the ancient spice trade from Arabia into Europe. It was they who pioneered sea-based transport up the Red Sea. It was they who became so fabulously wealthy as middle men that the Romans had to invade and conquer them to get in on the trade. It was they who gave the Arabic alphabet most of its letters. It was they who were by far the best adapted Arabs for handling the larger world around them in the centuries before Islam. It was they who worshipped at many cube shaped temples called a Ka’ba. We will talk in depth about Petra later.

Now let’s focus back on the two enigmatic references to Makkah/Bakkah for a moment. Makkah/Bakkah is further described in surah 3:95-7 as the spot where Abraham stood. Pilgrimage to the house is a duty to Allah for all who can make the journey. This is clearly the role Mecca plays today, but contrary to Islamic tradition, there is not a scrap of objective historical evidence that Abraham ever went to the Arabian Peninsula. So where was Makkah/Bakkah? History records that Abraham lived at Beersheba in the Negev desert in southern Israel, as did his immediate descendants including his first-born son and the ancestor of the Arabs, Ishmael. Another son of Abraham was Midian. One of the sons of Ishmael was Nebaioth, ancestor of the Nabataeans. The Syrians are descended from Abraham’s brother Nahor. The Jordanians are descended from Abraham’s nephew Lot. These ancestors of the Arabs all lived in the Levant, not lower Arabia.

In times concurrent with the rise of the Arab Empire these descendants of Ishmael had a famous pilgrimage site close to Beersheba, near Abraham’s great oak of Mamre. They all knew where to go to honour their combined ancestor. An excellent description of this place comes from Sozomen’s Historia Ecclesiastica, chapter 4. So it seems logical that the original Makkah/Bakkah could also be located close to Midian, Ad and Thamud in the region of the Negev Desert and lower Jordan.

In addition to this hard evidence, all mosques in Islam’s early years actually faced Petra, not far from Mamre, and were then switched to face Mecca at a later date in the 8th Century. Yes you read that correctly. They all initially faced Petra, not modern Mecca. The Qur’an even records this change in direction for prayer, called the qibla which is Arabic for direction, from the north to the south in surah 2:143-4. But as usual the Qur’an it doesn’t say from where it was in the past to where it was to be in the future, or even when the change took place. Significantly, the oldest Qur’ans do not have Surah Two, so do not mention this change of direction. On the other hand the Hadith literature kindly and conveniently declare that it took place early, during the life of Muhammad in 624AD to be precise, and was a switch from Jerusalem to modern Mecca. None of this information is in the Qur’an. I will explain more about this change of direction toward the end of the essay.

The view that Makkah/Bakkah was in northern Arabia and not central Arabia is strengthened by the reference to a place called Baka in Psalm 84 of the Old Testament:

Blessed are those who dwell in your house; they are ever praising you. Blessed are those whose strength is in you, whose hearts are set on pilgrimage. As they pass through the Valley of Baka, they make it a place of springs; the autumn rains also cover it with pools. They go from strength to strength, till each appears before God in Zion.

Below I will line up the two Qur’anic quotes about Makkah/Bakkah so we can compare the three together:

Surah 3:96-7: Indeed, the first House [of worship] established for mankind was that at Makkah – blessed and a guidance for the worlds. In it are clear signs [such as] the standing place of Abraham. And whoever enters it shall be safe. And [due] to Allah from the people is a pilgrimage to the House – for whoever is able to find thereto a way.

Surah 48:24. And it is He who withheld their hands from you and your hands from them within the valley of Makkah after He caused you to overcome them. And ever is Allah of what you do, Seeing.

After reading all three references, you will notice similarities. They refer to a house of God. They refer to the valley of Baka/Bakkah/Makkah. They refer to a place of worship. But then there’s the mention of autumn rains covering the valley with pools of water in Psalm 84. Mecca has virtually no rain, let alone autumn rains. It receives only a total of 50 millimetres in those three months on hot baked ground. Baka was not Mecca by any stretch of the climatic imagination.

Could it be that the Qur’anic references are a plagiarised version of a poem written some 1,500 years earlier referring to Jerusalem, often called Zion in the Old Testament? Could this be why Abd al-Malik, king of the Arab Empire from 685-705AD built his ultimate statement of the emerging religion, the Dome of the Rock Mosque, on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem itself which many believe to be exact spot called Zion? After all some 7% of the Qur’an is plagiarised passages from the Old Testament. Additionally, the temple Abd al-Malik built on the Temple Mount faced Petra and still does. Abd al-Malik cleverly combined the Jewish, Christian and Nabataean pagan Ka’ba holy sites.

The fact that the Qur’anic references say absolutely nothing about Makkah/Bakkah’s location being in Arabia or about its precious Ka’ba is to be expected. Modern Mecca is completely missing from all maps, inscriptions, trade notes, graffiti, official documents and church records for the period up to the middle of the 8th Century, It is only in 741AD, some 110 years after the traditional death of Muhammad that Mecca first appears in the Apocalypse of Pseuido-Methodius Continuato Byzantia Arabica. It doesn’t even appear on any maps until 900AD.

The Qur’an does, however, contain some more subtle clues as to the location of Makkah/Bakkah. Let’s now look at those clues.

Although the Qur’an is almost totally absent in geographical references, it does talk about a military defeat of the Byzantine Empire and specifically says that it was in a nearby land (Q 30:1-2). The fact that this defeat happened close to where the Qur’an was written raises significant questions about where the author of the Qur’an lived. You see, the Byzantines never ventured deep into the Arabian Peninsula, but they had already conquered and occupied Nabataea hundreds of years earlier, and were in control of Palestine, Syria and Jordan at the time of the birth of the Arab Empire.

Next, the Qur’an talks about the old woman who was left behind and became a pillar of salt when Lot and his family escaped the city of Sodom (Q 37:133-38). What is interesting is that the location for this event was universally held to be near the Dead Sea, and the writer of the Qur’an says that his readers pass by these ruins day and night. This places the location of the writer far closer to Israel than Mecca, some 1,300km to the south.

And there’s more. All Islamic commentators claim that Muhammad was a trader who frequented the lands of Palestine and Syria. Trade routes were the freeways, railways and internet of their time. For the record though, Mecca was not on any known historical trade route, none. On the other hand the Nabataean capital of Petra had been in the past the hub of several very important trading routes connecting Europe to Asia from east to west, and Europe to Africa/Arabia from north to south. It had a major trade highway to Damascus in Syria. That’s the only way Muhammad, if he grew up in Petra, could have been a trader with the Syrians. Petra was wealthy. Petra was influential. That’s why the Romans took it in 106AD. If Muhammad, the trader, came from somewhere else than modern Mecca then the logical place is much closer to the known trade routes further north. The story tellers that created the Sira and Hadith were using historical memory of Nabataean glory to project a plausible history of trading and spiritual significance down into the Hejaz and Mecca.

How could all this lack of evidence and contradictory evidence for the location of modern Mecca be sitting under our noses all along? Yet we are still just scratching the surface. In the rest of this essay we will explore Mecca’s geography, the statements of ancient historians, the flow of ancient trade routes through the Middle East, the actual commodities traded at that time and where they came from, the real location of ancient Arab religious sanctuaries, the political allegiances that shaped the Middle East in the era of the birth of the Arab Empire, and the shifting religious currents that created Islam. These evidences will give you a thorough understanding of the true history of Mecca, or lack thereof. Let’s start with modern Mecca’s location and climate.

5. MECCA’S GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE

Mecca is situated some 80 kilometres inland from the port of Jiddah. It is a barren, desert area, with small rocky hills jutting out of a flat sand-filled plain. It is devoid of forest, any oasis and accompanying grass and trees. It therefore had no timber to build with and no ships for trade. Because of its harsh climate, Mecca also had no agricultural hinterland. The logic of this fact forces us to rethink the whole concept of Meccan trade. How would massive camel caravans of a thousand or more animals have been replenished in such a barren place? Mecca only receives about 110mm of rain a year over an average of 22 days, or about 6mm per rain event. Rain was indeed a novelty. There was therefore no feed for livestock, let alone food for people. Barren places off the beaten track do not make natural sites for stopovers on international trade routes, let alone cities of trading empires producing armies of up to 10,000 men.

Yet Mecca is said by the Hadith literature to have been at the crossroads of significant international caravan trade routes. This is a complete fabrication as it is missing from all trade maps until the 9th Century. This lack of evidence makes sense if you consider that sea transport was vastly cheaper than land transport in late antiquity, and still is. Why would cargo be unloaded at Jiddah, taken 80 kilometres east to Mecca, then 80 kilometres further east and 1,500 metres up the mountains to the plateau town of Ta’if, then north toward the Mediterranean via overland camels when it could have continued in bulk by sea at a much faster pace? What a prohibitive and uncompetitive cost to the merchants receiving Meccan produce or spices! The need to provision such enterprises makes it without question physically impossible for trade to have originated from Mecca, or even transited through, as everything imported would have been very expensive. Making a profit via the uncompetitive overland trade route would have been utterly impossible.

In light of the above logic it is indeed surprising that the Qur’an also talks at great length about agricultural practices and the raising of livestock in the vicinity of its writer, who it claims lived in Mecca. These practices did indeed exist at and around Petra due to elaborate irrigation systems. Dry-land cereal cropping also existed in the upper Negev desert and lower Jordan. I have personally seen marginal grain fields around Beersheba at sowing time. In contrast, Mecca is totally devoid of any agricultural hinterland and associated livestock farming. Incredulously, the writer of the Qur’an, who was supposed to have lived in Mecca even talks about grape vines, olives, grain, fruit trees, dense shrubbery and fresh herbage (Q 80:27-31). This is in spite of the fact that olives are impossible to grow in the oppressive Meccan climate. But in the northwest corner of Arabia at Nabataea, in the lower Jordan and the upper Negev, agriculture flourished and it was even possible to grow olive trees. Why else would Abraham have settled there? It is looking more and more likely that the writer of the Qur’an lived somewhere else than modern Mecca and this city was theologically moved to central Arabia after the facts. The Qur’an itself suggests so.

On top of those significant agricultural contradictions we are told Mecca was a centre of pilgrimage with thousands flocking in for the religious festivals with their animals. I will talk more about this later, but let me just say that this would only compound the problem of food supplies. Crone says that when we first hear of Mecca as a pilgrimage site it is in the new Muslim era and not before. We also find they were importing grain from Egypt to feed the pilgrims, by sea of course. The more people we place in Mecca the more imports we must generate to sustain life there. All these difficulties vanish if we locate the Arab trading centre closer to established centres of agriculture, as the Qur’an points to.

Finally, in the era before the Roman Empire there was indeed an inland caravan route from Yemen to Palestine. It followed the elevated edge of the Sarawat Mountains, which run parallel to the coast all the way up the Red Sea. Yet Mecca is on the coastal plain, well over a kilometre in altitude below this inland route. Why would a caravan deviate some 80 kilometres from Ta’if, which was on the inland route and capable of resupplying a caravan with food, drop 1,500 meters in altitude down a canyon to barren Mecca, and then crawl back up to continue their journey? This would make absolutely no commercial sense.

6. WHAT THE ANCIENT HISTORIANS HAD SAID ABOUT MECCA

There are two pieces of evidence that Islamic historians hold strongly regarding their claim that Mecca existed in pre-Islamic times. The first is a quote from the ancient Greek geographer Pliny the Elder who charted the coastline of Arabia. In Natural History he mentions in Book VI a place in Arabia called Mochorbae. This would push Mecca’s existence back to early in the 1st Century. The second is Ptolemy’s longitude and latitude coordinates for a place in Arabia called Makoraba. Unfortunately many western scholars lazily accept the Muslim claims that these two towns both represent the Qur’anic Makkah/Bakkah and therefore modern Mecca. Let’s now critically examine these claims.

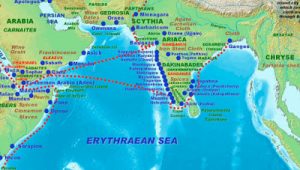

In Natural History Book 6, 149, Pliny specifically says Mochorbae is a port on the coast, not an inland town which would be the case if describing modern Mecca. He also says the towns of Homma and Attana are the most frequented in that area, which he then names as the Persian Gulf! Mochorbae was therefore nowhere near modern Mecca. He then says Mochorbae lies just up the coast from the islands of Etaxalos and Inchobrichae, near the Cadaei tribe and the Eblythaean Mountains. This also puts Mochorbre nowhere near modern Mecca because Homma (Ommana) is in modern day Iran, while the latter references were in Yemen on the South Eastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula. You can see a guide to Pliny’s location for Ommana on the map below. Pliny’s Mochorbae is nowhere near todays Mecca.

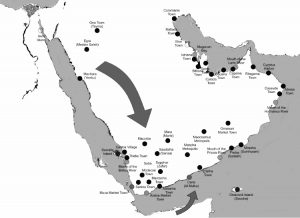

A hundred years later Ptolemy, the inventor of the concepts of longitude and latitude, gave the world specific coordinates for a place called Makoraba in the Arabian Peninsula. It is shown on this map, just right of the fork in the major river, if you zoom in. It is a vaguely similar name and located in a vaguely similar place to modern Mecca. So far, so good. However, it is not modern Mecca for the following nine reasons:

First, it should be noted that at the time of Ptolemy the Arab language did not exist, so two towns starting with M, but with very different names, some 500 years apart in different languages is likely just a coincidence. To illustrate: Arab words nearly all start with a three consonant root (it is the same with Hebrew and that is why Yahweh in the original is yhwh). Patricia Crone says the three letter root krb from which Makoraba is derived is completely different from the root mkk from which the Qur’an’s Makkah is derived. Second, Ptolemy also Hellenised a lot of the names he used for his lists so his names would not match local names. Third, Ptolemy locates Makoraba right where Medina is today, which was called Yathrib in ancient times. This is some 400 kilometres to the north of modern Mecca. Nothing exists on his list of coordinates in the location of Modern Mecca that resembles its name on the map. Fourth, Ptolemy never visited most of the inland places he created coordinates for, he instead relied heavily on local traders for information about inland towns. Fifth, as expected Ptolemy was very accurate for locations around the Mediterranean but became less accurate as he gave coordinates for places further afield, such as Arabia. Sixth, Ptolemy was very accurate with latitude, but very inaccurate with longitude. This resulted in him miscalculating many places in Yemen at the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula. Seventh, if Ptolemy’s map is accurate, Makoraba does not match any known trade route or pilgrimage site of that era of that name. Eighth, Ptolemy exaggerated the size of Yemen because of its spice trade significance to Europe in the 1st Century, thus pushing all other towns in Arabia to the north of where they would naturally lie.

Finally and most importantly, the only river (wadi) on the map above, called the Betius River, must by necessity correspond with an existing wadi today. Cities come and go but rivers just keep flowing. The only Wadi of significance on the South West Arabian coast, Wadi Mawr, is actually 500km south of Modern Mecca. If you rejig Ptolemy’s very loose longitude coordinates to match rivers, most towns are suddenly located accurately and Makoraba becomes Al-Mahabishah. You can find an excellent extended article by Dan Gibson on the above list of points at this link. I have reproduced his map of Ptolemy’s original and corrected coordinates below.

Ptolemy’s original coordinates

Ptolemy’s corrected coordinates

To add weight to the argument that Ptolemy was not describing the Makkah of the Qur’an, I have reproduced below a 1st Century Roman trade map according to the Periplus Maris Erythraei, confirming the non-existence of any trading towns anywhere near the vicinity of modern Mecca. If Mecca was a real trading city in the era of Ptolemy it would be on this map!

In addition, Procopius of Caesarea was a prominent Greek scholar of late antiquity and the leading historian of the 6th Century. He does not mention Mecca in any of his writings, which is strange if it was a significant commercial centre and the main link in trade between India and Europe just before the rise of Islam. In fact no non-Muslim historians mention Mecca at all in the 6th or 7th Centuries. It is completely missing in action.

It gets worse. Crone says no non-Muslim Arab historian of the same era mentions Mecca either and there are no surviving Arab records of trade via Mecca before the 8th Century, seventy years after the birth of the Arab Empire. This silence extends to any mention of the Quraysh tribe, who were the prominent traders from Mecca and from whom Muhammad is supposed to have come from. All this in an era when there were extensive writings about the South Arabs, the Yemenis, the Ethiopians and the Adulis, a people who occupied the coast opposite modern Mecca. Crone says this silence extends to all records in “Greek, Latin, Syriac, Aramaic, Coptic or any other literature composed outside Arabia before the Arab conquests” (Meccan Trade p. 134). She should know as she could read documents all of those languages in their original state.

The ancients have spoken, and they do not mention Mecca anywhere.

7. HISTORY OF THE ARABIAN SPICE TRADE

But what if, just by chance, Mecca actually did exist outside the knowledge of all those witnesses. If it was indeed a thriving trading town, then what commodity did it trade that would cause it to prosper? What commodity was produced in Arabia or nearby that could have been traded by the Meccans north to the huge Byzantine markets? What commodity would have survived a long overland journey in such a hot, barren environment? What commodity was worth enough to take the risk of raids and theft? What commodity was valuable enough to justify camels taking 60-70 days to reach the Mediterranean? The goods must have been therefore very rare, very light, highly coveted by the Romans and then by the Byzantines, so making it very expensive and lucrative.

The obvious and only answer to all of the above questions is the exotic and coveted spices such as frankincense and myrrh. These were aromatic lumps of dried resin from two species of tree that grow in the rugged mountains of Yemen. They were indeed desired by pre-Christian Romans for their lavish pagan temples, their related religious festivals, opulent Roman lifestyles and acclaimed medical benefits. The first trade in these commodities is said to have begun when the Queen of Sheba visited King Solomon. One Kings chapter 10 in the Old Testament describes the precious spices the beautiful queen brought as gifts to Solomon. She would have come up from the Sabean capital of Ma’rib in Yemen to Palestine through what would become a significant inland commercial highway from Timna, Sana’a and Baraqish in Yemen, through Najran in Southern Arabia, to Yathrib (Medina) then on to the oasis of Khaybar and eventually on to Petra.

From there we jump to the Greek era and this is when we know the trade really took off. In the centuries before Christ spice trade traffic and profits were dominated by the Nabataean Arabs based in Petra, and we hear from Hieronymus of Cardia that the Nabataeans “were accustomed to bring down to the sea (the Mediterranean) frankincense and myrrh and the most valuable kinds of spices which they procure from those who convey them from what is called Arabia Eudaemon” (Diodorus Siculus, Bibliobeca Historica, xix, 95:5). This is the first European mention of the overland route. There are several other reports of an overland route through Arabia to the Mediterranean in a trade that thrived from the time of Alexander the Great onwards. However, Pliny the Elder who we met above, is the last to mention frankincense and myrrh being transported via the overland route from the mountains of Yemen at the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula. It should be noted also that at this stage we are only talking about trade in Arabian and Yemeni goods, nothing came from India before the Roman era of high tech shipping.

The drier eastern side of Yemen’s amazingly rugged mountains provided the perfect climate for frankincense and myrrh, which came from the sap of the Boswellia tree, and the sap of the Commiphora shrub respectively, hence the inland trade route. The Romans were said to importing 3,000 tonnes a year at one stage. But even at this point in history the overland route only owed its existence to the refusal of the Yemeni mountain kingdoms to countenance sea transport. That politically motivated cost inefficiency soon created a rival source of spice supply with the convergence of interests between the coastal-based Himyarite kings and the newly sea-faring Nabataean middle men. In time a competitive supply of spices also opened up from Ethiopia.

By the end of the 1st Century there is no longer any mention of an inland spice and trade route. At a fraction of the cost of camel train, all goods were shipped by sea to the Nabataean port of Lueke Kome in the Red Sea Gulf of Arabia, or Myrus Hormus in the Suez Peninsula closer to Egypt. They were then hauled a short distance overland to the Mediterranean for reshipping to Europe.

Because this was a lucrative choke point in all trade between India, Ethiopia, Arabia and their rich religious customers in Europe, the Romans decided to conquer the Nabataean Arabs in 107AD. They then dominated the whole spice trade, developing the navigational skills to take ships right through to India, thereby cutting out all middlemen in the process. It was one of these trade ships that took the Christian Apostle Thomas to India in the 1st Century. The Yemeni port of Aden became the natural midway point for ships coming from both directions, and remains so today. This made Southern Arabia vulnerable to imperialistic ambitions, resulting in its eventual conquest by the mighty Persians.

Eventually all good things come to an end and the whole historical chapter of the spice trade collapsed with the Christianisation of the Roman Empire and the rise of the Byzantines. The ostentatious behaviour of the Roman elite and their pagan temples was not becoming in the Christian era. By the 6th Century the spice trade had practically ceased altogether, being replaced with low value Arabian hides and naphtha (flammable oil). The trading of frankincense, myrrh, cancamum (incense gum), tarum (aloe wood), ladanum (perfumed resin) and sweet rush (essential grass) soon became just a historical memory.

By the time of the alleged rise of Mecca as an influential inland trading centre, the concept of a land-based trade route through Arabia from south to north was nothing more than a historical memory, one resurrected in the 9th Century construction of Islam’s and Mecca’s origin myths. Historians of late antiquity such as Cosmas the Monk, while on his way through to India, failed to even note that the Byzantines imported any Arabian spices (Topographie, II, 49). Other historians such as Jacob of Edessa (Ashley: Use of Incense, p.101), and Procopius (History of the Wars Books I & II) only talked about Christian missionaries and tribal disputes within Arabia while always referring to the spice trade in the past tense. Without a spice trade there is no wealth for Mecca. Without wealth there is no army to launch conquests of the Middle East. Understanding history means following the money trail.

8. WAS MECCA A PILGRIMAGE SITE?

According to the Sira and Hadith histories, another reason why Mecca existed in the lead up to the sudden and divine birthing of Islam was its strategic location as a pilgrimage site where people came to the Ka’ba to worship a multitude of pagan gods. Muhammad’s great revelation was that these idols were mute and that Allah alone, which happened to be his tribal diety, was the creator of the universe. Thus Islamic monotheism was allegedly divinely born in the midst of polytheism in a place completely cut off from traditional centres of monotheism such as Palestine. Islam wants us to believe its monotheism came from above, not from the north west.

On top of the many already highlighted in this essay, another problem with this story is that it ignores the history of the 16 major pagan pilgrimage sites and festivals that existed in the Arabian Peninsula at that time (Marzuqi, Azmina, II, 161, Ibn Habib, Muhabbar pp. 263, Abu Hayyan, Imta, I, 83, Yaqubi, Ta’rikh, I, 313). Pilgrimage sites in much of Arabia were temporary sanctuaries, often open-air, the natural features of the spot being sufficient to distinguish it. They were deserted most of the year and would come alive with transient Bedouin Arabs during their respective religious festivals. They were not frequented once a week or every day as per the official descriptions of Mecca have come down to us.

These pilgrimages would be made at certain fixed times of the year. They were neutral locations where different tribes downed arms and nobody was in control. Arabs were a largely nomadic people, so pilgrimage festivals at the site of their favourite diety were a natural fit to their lifestyle. The Sabaeans were, for example, noted for an annual procession to the temple of Almaqah in Ma’rib at the time of the summer rains.

What did they do at these festivals? Robert Hoyland in his book Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam, pages 157-162 quotes two ancient historians who tell of what went on. Hoyland quotes Tawhidi 1.85 as saying they would stage poetry competitions and debating contests and settle their differences. Whoever had a prisoner would work to ransom him, and whoever had a lawsuit would submit it to the member of Tamim who was in charge of legal affairs. He also quotes Antoninus Placentinus 147, 149 as saying Nothing was sold, for they considered that anathema while they were celebrating their holy days.

Crone says that a pilgrim sanctuary owned by a specific tribe is unknown in the literature. In addition, not one of the 16 pilgrimage fair sites of major importance includes the name Mecca. An additional problem was that at these sites trade was officially suspended during these fairs, so if Mecca was a pilgrim site it could not also have been a flourishing centre of trade, as claimed by the Hadith and Sira. The list of the very few places run by pagans that did continue to trade during festivals also does not include Mecca. The major pilgrim stations in Arabia were Mina, Arafa, Ukaz, Majanna and Dhul-Majaz (Hoyland p. 162). Although the first two sites are very close to the location of Modern Mecca, and thereby give us a clue as to why Mecca eventually arose in that vicinity, the words Mecca/Makkah/Bakkah are once again missing from the original lists. So the idea of Mecca being a pilgrimage site supercharged as a major international trade centre of considerable size is not supported by the local Arab historical sources.

This highlights three problems. First, guardians of a sanctuary could not have also made a living as traders. The two functions were mutually exclusive, just think of the Hebrew or Greek priests as an example, in most ancient religions temple guardians were people set apart. Second, the description of Muhammad’s tribe, the Quraysh, that is given us in the Islamic traditions does not include the services expected of guardians of a pilgrimage site. These services, in parallel with the Greek holy sites and many others, included professional divination. The name of Muhammad’s tribe is also missing from the historical literature. Third, we are left wondering which god the Quraysh protected. In the Islamic traditions they go into battle against Muhammad invoking idols, while at the same time we are told they were guardians of the diety called Allah. The Islamic traditions are therefore contradictory, ascribing at the same time both monotheism and polytheism to the Quraysh. Oh, and don’t forget that not a single mosque faced Mecca until 724AD, so it held no significance as a pilgrimage site.

Although I have now demonstrated beyond doubt that the Arabs did not worship at Mecca in the lead up to the birth of the Arab Empire, they did in fact have a history of worshipping Abraham and monotheism at another very special pilgrimage site. Arabs and Jews alike had long worshipped and feasted in the name of their God and their common ancestor Abraham at a place in Palestine called Mamre, near modern day Hebron. The Jews and the Arabs shared Abraham as a common physical ancestor through Abraham’s two sons Isaac and Ishmael, while for the Christians Abraham was also a spiritual ancestor. This is the very place where the Bible says Abraham was visited by three angels under a great oak tree (Genesis 18:1-2) and near where both Arabs and Jews to this day say that Abraham is buried. The combined efforts of Roman Emperors Constantine and Justinian to stamp out pre-Islamic pagan worship from this place proved fruitless. The Khuzistan Chronicle of the middle 7th Century acknowledges that Arabs who worshipped there (in the years when Muhammad was supposed to be preaching further south) did so out of reverence for Abraham, the head of their nation. Perhaps the best description of worship at Mamre Comes from Sozomen’s Historia Ecclesiastica chapter 4.

Could it be that Islam’s insistence that theirs was the true religion stems from this very site or somewhere in that region? After all, the Qur’an in Surah 3:96-7 insists that Abraham built the first true temple and that Makkah/Bakkah is the true site of that temple. This spot is in Abraham’s backyard.

As we have already noted, there are three clues in the Qur’an telling us where this temple might be: The Qur’an says that agriculture flourished around Makkah (Q 80:27-31), the Qur’an describes a defeat of the Roman Empire in a nearby land (Q 30:1-2), and the Qur’an talks about nearby location of the old woman who was left behind when Lot and his family escaped the city of Sodom and became a pillar of salt (Q 37:133-38). All of these sites are in lower Palestine or Jordan, the very spot where Abraham lived.

9. BIRTH OF THE ARAB EMPIRE

So what was actually going on in the Arabian Peninsula at the time of the supposed rise of Islam from the city of Mecca? If the spice trade did not exist, if Mecca was missing from maps and trade records, if the Qur’anic description of the geography of Bakkah is very different to modern Mecca, if ancient European and Middle Eastern historians didn’t ever mention it, if all mosques faced Petra, if there was no pilgrimage site at Mecca, if the peoples described in the Qur’an all lived in lower Jordan, and if Qur’anic references describe a completely different climate than modern Mecca, then the Sira and Hadith literature were clearly mythologising the past. So what on earth was actually happening?

We will now dive into the true story and briefly reconstruct it.

As mentioned already, the two major empires, the Sasanian Persian Empire, and the Roman Empire that morphed into the Byzantine Empire, took great interest in Arabia. The Persians had colonies throughout eastern and southern Arabia, the Najd and in Yemen. Their western sphere of influence extended to the Syrian Desert and the Hijaz in south west Arabia where Mecca is today. The Byzantines had no colonies south of Tabuk but their sphere of influence was felt throughout western Arabia and the Syrian Desert where they had client kings. Their Ethiopian allies also had control of Yemen until they were expelled by the Persians. Arabia was thus at that time subject to a level of foreign control not seen again until the modern colonial era. The Arabs were a subjugated people and must have felt a stinging loss of sovereignty.

Yet in spite of this situation, some Arabs lived a very integrated and privileged life within the two empires. In the centuries before the rise of Islam many Arabs had migrated northwest to either the Byzantine province of Syria, or northeast to the cities of the Persian Empire. As always with migrants, they were seeking a better life and trading opportunities. On this point even the Islamic sources agree with the external sources about these migration and trading activities! Eventually these migrants, with their Arab love for war, emerged as the two deputised and opposing proxy kingdoms and armies in the endless frontier confrontations between the Byzantine and Persian Empires. The most prominent were the Ghassanids and the Lakhmids. These two groups had prospered in their adopted homelands and their leaders became client kings within the elite of their respective empires.

These people would become the true source of the mighty Arab armies that swiftly conquered the Middle East in the 7th Century. After the great Byzantine-Sasanian War of 602-628AD completely and finally destroyed the Persian Empire and massively weakened the Byzantines, there was a enormous power vacuum in the Middle East. Enter the Arabs, free of colonial control at last and on a mission to control and subjugate the very lands of their former imperial masters. And who can blame them, what an opportunity!

Their conquests were both politically and religiously motivated, but not by a religion called Islam in the crucial first century of their empire. But first let’s consider the following calendar and curious parallels between traditional Islamic history and actual events: Muhammad’s revelations are supposed to have started in 610AD, the same year of Heraclius’s capture of the Byzantine throne in Constantinople. The story dating the prophet’s flight to Medina in 622 AD is the same year the Byzantines swept down through Anatolia and Syria, putting the Arab-led Persian army to flight after the battle of Issus. The story of the conquest of Medina in 627AD, called the Battle of the Trench, synchronises with the Byzantine Emperor’s 627AD triumphant conquest of Persia. The 628AD peace treaty between Mecca and Medina is the same year of the peace treaty between the victorious Byzantines and the utterly defeated Persians in 628AD. Finally, the Persian multi-ethnic Arab-Christian city of Al-Hira is recycled as Hira, the cave where Muhammad received his instructions to form a religious community that transcended cultural boundaries.

The political vacuum created by the fall of the once mighty Persian Empire was soon filled by their Arab minions. The weakened status of the Byzantines invited further challenge from the Arabs in the west. They literally fell into a tailor-made Middle Eastern empire. From there the Arab’s march across the Middle East, Africa and up into Central Asia was relentless, decisively pushing back the remnants of the Persians and crippling the might of the Byzantines. They pressed their advantage perfectly. It was only hundreds of years later that this was retrospectively seen as the blessings of their new prophet and holy book.

It is therefore no accident that Palestine, Iraq and Syria, but never Arabia or Mecca, were the natural bases for all early Arab imperial leadership. That’s where the Ghassanids and the Lakhmids were based. They never based themselves in never Mecca. The first major dynasty of the Arab Empire, the Umayyads, who were supposed to have come from Muhammad’s own Quraysh tribe no less, had a history of living in Syria not Mecca. They traded with the Byzantines and invested profits into local real estate, a history that suggests close contact with the frontiers of an empire, not the depths of an Arabian desert. Damascus was their capital and the shrine of John the Baptist was their most holy site. Their most influential leader, Abd al-Malik, moved his capital from Damascus, but not to Mecca. He went to Jerusalem. Jerusalem was seen at this time in Arab imperial history as the trophy city. If Mecca existed and was the most holy of cities then it is indeed curious why Abd al-Malik moved the capital to Jerusalem. The next Dynasty, the Abbasids ruled from Baghdad, not Mecca. It was no accident that this new city was just a few kilometres from Ctesiphon, the former capital of the Persian Empire.

Mecca was never the natural home for any Arab leaders for hundreds of years after they launched their empire in the gap created by the collapse of the Persian Empire and the near collapse of the Byzantine Empire. This is because Mecca did not exist until at least the early 8th Century. It was in the wildernesses of no man’s land compared to the wealth and power of the civilisations of the Fertile Crescent.

10. BIRTH OF THE ISLAMIC RELIGION

Now let’s examine more closely the religious motivations of the Arabs. The Syrian-based Arab Ghassanids were Syrian Orthodox Christians through and through. The Persian Lakhmids in Persia were less so but were surrounded by the strong and influential Nestorian church. Several centuries earlier the Arabian Peninsula had become yet another region impacted by a rapidly growing Christian religion as it spread throughout its birthplace of the Middle East, then to Africa, Europe, England, India, Sri Lanka, Central Asia, Persia, Afghanistan, Mongolia, and even through to China, all before the rise of Islam. The Persian Gulf, although still largely pagan and full of pagan festival sites, was very familiar with Christianity in that era of the emergence of the Arab Empire. Syria and Palestine were majority Christian. The irrepressible Jews were outnumbered in their own land, but had lived in many scattered communities throughout the Middle East since the era of their Babylonian captivity in 539BC. Contrary to Islamic tradition, monotheism was very well known to the Arabs.

The initial flush of Arab imperialism was largely Christian too, but a Christianity that was at theological and political war with the Byzantine imperial Catholic church and government. In the eyes of most clergy from the Middle Eastern Orthodox traditions, the Catholic Byzantines had corrupted the Christian religion with idols of saints, veneration of iconic images, the worship of Mary, and the hideous theology of the Trinity. They had a point! Middle Eastern Christianity was much more austere and followed the teachings of Arius who rejected the Trinity in favour of seeing Jesus as a lesser being, a messenger for God, but not actually God himself.

Traditional Islamic history says that Muhammad’s father was called Abd-Allah, meaning servant of God. This very term was actually in widespread use in coinage in the first half century of the Arab Empire as a reference to none other than Jesus Christ. Also in use on Arab imperial coins was the term MHMT with the cross on the inverse side of the coin. This was the first objective historical reference to Muhammad and came in the late 7th Century under the reign of Abd al-Malik in Jerusalem. At this stage Abd al-Malik was connecting the term MHMT, which means Praised One, with Jesus Christ instead of a prophet called Muhammad from the depths of Arabia. Over time these beliefs about the unity of God and the inferior status of Christ would evolve to became the core teachings of Islam as it metamorphosed into a separate belief system.

This evolution of Islam out of Syrian Christianity is further evidenced by the fact that a huge amount of the material in the Qur’an is a vitriolic attack on what it perceives as shirk; the sin of practicing idolatry and associating other lesser beings, in other words Jesus and Mary, with God. There are over 15 references to shirk in the Qur’an, and over 40 references to the Mushrikun; the people who practice shirk. Several thousand verses talk in an “Us against Them” manner. Around a thousand tell the reader they better believe what the Qur’an is telling them, or else. Fear is also a central theme, with around 250 verses advising the reader to fear God or face the consequences. The word punishment appears around 350 times. The context of the Qur’an was clearly a huge division between two similar theologies competing for the loyalties of the Arabs. The language of the Arab Qur’anic argument was threat, coercion and fear of punishment for non-obedience. It remains so today.

Traditional Islamic history says these references and threats are addressed to idol worshippers deep in Arabia around Mecca as at that stage they had no dealings with monotheists. However, the Qur’an specifically mentions shirk in relation to Jesus as the begotten Son of God (surah 112) as well as praying to saints and angels, which was the practice of the Byzantine Catholics that they adopted from Greek and Roman pagan practices. Placed alongside the many blistering attacks on Christians as the people of the Book in the Qur’an and the polemical attack on the divinity of Christ inside the Dome of the Rock Mosque in Jerusalem built in 691AD, it is clear that the theological roots of Islam were embedded in a theological war for the soul of Middle Eastern Christianity. If you needed any more proof that Islam was birthed as an angry polemical attack on Trinitarian Christianity and not pagans deep in the Arabian Peninsula first read all of surah 2 or 9, then then consider the following: Moses is mentioned 136 times, Abraham 66 times, Aaron 24 times, Adam 25 times, Isaac 17 times, Jesus around 24 times, Lot 27 times, Solomon 17 times, but Muhammad only 4 times.

The switch from Arian Christianity to a fully-fledged Islamic religion took place slowly in the years from 685-800AD. The Arab Orthodox monk John of Damascus, who was active in the Umayyad administration at the time of Abd al-Malik, records in Heresy No 100-105 that the prophet of the new religion had conversed with an Arian monk. However, most of the fossilisation of Islamic theology came after the Persian Abbasids took control of the Arab Empire in 750AD and moved the imperial headquarters from Jerusalem to Kufa in Iraq and then quickly to their brand new capital city of Baghdad in 762AD.

Why did the theology evolve so far away from its Christian roots? The answer lies with the nature of empires in that era. All empires throughout history need a justifying theology or ideology. However, for its first 60 years, until around 690AD, the newly hatched Arab Empire lacked what every other empire had in that era; a potent and politically justifying theology of its existence and destiny. The Arab Empire was still inside the Christian religion, the religion of their enemies, the Byzantines. The Arab Empire therefore eventually built itself a new and triumphant religion around the Arabic language, an Arab prophet, an Arab book and an Arab holy city. Arabisation of the new religion would be the defining and unifying factor in its future history.

Because the empire came from a Christian background, their new religion would by default reflect the theology of that old religion in so many ways, but would need to reject it in so many others in order to become independent. This explains the Qur’an’s relentless attack on Catholic Christianity and the need for Islam to relentlessly wage war on Christian Europe for the next 1,400 years, a war that has gone up a notch in the last 30 years. The European heartland of Christianity represents a mortal threat to Islam’s unequivocal and opposite claims to truth, and the ultimate prize if won. For far more detail on this war I recommend you read my essay called Islam’s Rise and Fall.

This metamorphism to a new Arab-centric religion began in earnest under Abd al-Malik who transformed Muhammad from a title of Jesus to an actual man. It was he and his ruthless governor of Iraq Hajjaj ibn Yusuf who gathered together a collection of short religious recitations and fragments variously called The Cow, or The She Camel, into a complete Arab holy book (Did Muhammad Exist p.197-8). It was he who enforced the use of Arabic over Greek inside his realms and on his coins. It was he who invented the term Islam via the Dome of the Rock inscription to reflect his diverging theology. His crusade to create a new religion was eventually completed a century later via the mass mythologising of the past through the creation of the Hadiths and Sira literature under the guidance of the Persian legal scholars of the Abbasid overlords.

These facts alone explain why there is complete and absolute historical silence concerning a man called Muhammad, a book called the Qur’an, a city called Mecca, and a religion called Islam from any and all objective historical sources until the time of Abd al-Malik and beyond. This is a full 70 years after the “facts” of the birth of Islam were supposed to have unfolded in the bright light of history. It also explains why after this point there is complete silence regarding the role of Petra in the formation of the new religion.

For a far more detailed description of the emergence of the Arab Empire, Islam and its Christian roots please read my four essays titled Islam’s Linguistic Roots, Islam’s Christian Roots, Islam’s Pagan Roots, and Islam’s Theological Evolution.

11. THE LOCATION OF THE ORIGINAL ARABIAN CITY OF WORSHIP

We have now shown conclusively that modern Mecca is not the Mecca of history. So where was the original Arab city of worship? The obvious place to look is the city of Petra, of the Nabataean Arabs. Here are the clues we have gleaned so far:

Petra was the source of the Arabic alphabet. Mecca wasn’t.

Petra was a wealthy trading city on a crucial international trade route. Mecca wasn’t.

Petra was close to the pilgrimage sites associated with Abraham. Mecca wasn’t.

Petra was close to the site of the defeat of the Romans. Mecca wasn’t.

Petra was close to the site of the old woman turned into a pillar of salt. Mecca wasn’t.

Petra was close to Ad, Thamud and the Midianites. Mecca wasn’t.

Petra is far closer to the Bakka mentioned in the Old Testament. Mecca wasn’t.

Petra was the epicentre of Arab culture and civilisation. Mecca wasn’t.

Petra had cubic shrines called Ka’ba’s, and a sacred meteorite. Mecca didn’t.

Petra had extensive agriculture. Mecca didn’t.

But there is much more. The Greek historian Diodorus Siculus writes about Arabia in his work Bibliotheca Historica, describing a holy shrine: And a temple has been set up there, which is very holy and exceedingly revered by all Arabians. Claims have been made this could be a reference to the Ka’ba in Mecca. However, the geographic location Diodorus describes is in northwest Arabia, around the area of Leuke Kome, closer to Petra and within the former Nabataean Kingdom.

The Nabataeans had an affinity with geometry and often used a cube, or block of stone, as a point of reference for worship and to represent their gods. They even called these cubes a Ka’ba, which literally means cube. Their most sacred Ka’ba even held a stylised black stone, probably a meteorite, which fell from the heavens and was a gift from God no less. Modern Mecca’s centrepiece of worship is a still a cubed building housing that black meteorite. This is clearly a transferred Nabataean custom dragged all the way from Petra sometime in the distant past. If Islam was all about destroying pagan practices in the name of monotheism, it is very odd that this one distinctly pagan Nabataean practice survived to become the very epicentre of their religion.

The importance of Petra in the newly emerging Arab Empire is on display in every place of worship the Arabs build in the first century of their empire. It was natural and normal that every new religious building built until the 8th Century faced Petra and its most sacred of Arab religious sites, the holy Ka’ba. Early religious buildings oriented toward Petra included the Mosque of Amr ibn al-‘As in Egypt, the Great Mosque of Ba’albek in Lebanon, the Great Mosque of Sana’a in Yemen, the original Mosque of Amman in Jordan, the Umayyad Damascus Mosque and the Dome of the Rock Mosque in Jerusalem, and many others. If facing Mecca in prayer is a major function of Islamic religious practice since 624AD as claimed by the Hadith literature, then why does the archaeology of all ancient mosques built until 724AD clearly demonstrate that not a single mosque faced modern Mecca in that first alleged era of Islam as a religion?

It was only in 727AD that the first mosque, the Banbhore Mosque in Pakistan, was directed toward Mecca. For the next 98 years mosques faced both Petra or Mecca, half way between the two cities, or parallel between the two cities. It was not until 822AD that all new mosques finally faced Mecca, 1,300km south-south east of Petra. The directional evidence can still be seen in the structure and orientation of all ancient mosques and archaeological sites.

This raises deep and unsettling questions about the origins of Islam. The Qur’an only vaguely discusses the change in the direction of prayer (Q 2:143-4), with no place names or timeframe given. The official Muslim narrative says this event occurred in Muhammad’s lifetime, around 624AD. Whoever propagated this early date is telling a lie. The archaeological evidence cannot be argued with and it clearly says otherwise.

According to the historical evidence, and summarised beautifully in Tom Holland’s thoroughly researched and readable book, In the Shadow of the Sword, Mecca only slowly became a centre of pilgrimage from the time of Abd al-Malik’s suppression of a rival to his authority as king. The title Malik literally means King. Contrary to Islamic historical traditions there was no Caliph or Caliphate at this stage of the Arab Empire. His rival for the throne, Ibn al-Zubayr, had been in open rebellion since 680AD, first in Medina until it was sacked by Umayyad forces, then at a place only described as the House of God, the most sacred sanctuary and Ka’ba of the Arabs. This was destroyed by fire in the battle of 683AD.

Given that all Arab houses of worship faced Petra up until this point in time it is logical this house of God was somewhere in that vicinity, if not at Petra itself. Ibn al-Zubayr then fled down into central Arabia and built a new sanctuary for the sacred black stone safely away from the Umayyad kings at one of the traditional pilgrimage sites deep in the Hejaz, probably near to the sites of Mina and Arafa, very close to what is now modern Mecca. The Persian Abbasid Arabs hated their Umayyad overlords so gave their reverence to this new site immediately. Ibn al-Zubayr’s claim to leadership was now spiritual as well as political. It would take Abd al-Malik some years to defeat him. Victory finally came with a campaign led by Abd al-Malik’s general, Al-Hajjaj, into the Hejaz in 691-2AD, destroying the rebel, his army and his makeshift sanctuary.

To secure his authority in his opponents political stronghold, Abd al-Malik undertook a pilgrimage down into that province in 693AD. While there he visited Medina and then Ta’if, the birthplace of his father. From there he visited the nearby pilgrimage sites of Mina and Arafa, and the new site a few kilometres away, Ibn al-Zubayr’s new House of God. Abd al-Malik then rebuilt it. He could see the strategic advantage of keeping the black stone in this new site. He now controlled two sacred sites, the Temple Mount in Jerusalem and the new House of God that would eventually become Mecca. Some years later in 713AD an earthquake completely destroyed Petra for the last time and this sealed the future of the new site.